The Case for Copying: Ideas to Beg, Borrow, and Steal

Danielle Evans / WNW Member

“Good artists borrow, great artists steal” makes a glib tee shirt and inevitably begs a thousand questions about artistic theft. I believe there is a proper way to copy/imitate/inspire/attribute, but the industry doesn’t applaud people for broaching this subject. It’s true: everybody steals, myself included. Because I’m willing to admit I’ve participated in both sides of this argument, this makes me uniquely positioned to share my experiences, stealing and being stolen from. Welcome to my series on creative theft. Feel free to beg, borrow, and steal these ideas on copying the right way and the ongoing effect on the creative industry at large.

The Case for Copying

Never thought I’d say this: I’d like to make a case for copying.

I attended a tiny, unaccredited, private liberal arts school in the middle of nowhere, Indiana. All illustration students were required to take a master class, one where we replicated famous works to the best of our abilities and wrote up a report on the artist’s life and techniques. This course was an art kid’s wet dream since most of us grew up replicating work and copying reference photos perfectly.

My copy of a Malcolm Liepke from a college course next to the real deal. This lives in my closet.

The class came with one qualifier: try selling these works or adding them to your portfolio and face failure and/or expulsion.

We avoided comics and anime in this course and didn’t broach certain contemporaries based on their active professional status or relationships to our professor. Tempting as it was to chalk up the semester to a waste, students learned how to improvise from reference and had a trove from which to gift their grandparents “real art” for Christmas. When influences inevitably eked into work for other classes, we could tie these directly to masters studied and discuss whether these influences should be further diluted or not.

“Discussions surrounding copying are pervasive, i.e. ‘DON’T DO IT,’ but few safe spaces existed in which to explore. As with the topic of safe sex, how can we as a community expect to arrive at healthy decisions if abstinence is the only option?”

As far as I understand, my experience is highly unusual. Few if any accredited schools have a similar course, much less other disciplines like design or photography, which I find surprising. Discussions surrounding copying are pervasive, i.e. “DON’T DO IT,” but few safe spaces existed in which to explore. As with the topic of safe sex, how can we as a community expect to arrive at healthy decisions if abstinence is the only option?

Why bring this up? I think there are shades of copying that are beneficial, appropriation that benefits the borrower and the borrowee. Adversely, I argue that shades of theft are also detrimental. While the law punishes 1:1 copies, it doesn’t safeguard against damaging, highly unethical theft at various levels. For several years, I have grappled privately with a designer that has based her work squarely upon mine, making very good money imitating my style (from ligatures and typographic styles to lighting and styling, copywriting… even my bio was “adjusted”) while underbidding me in client negotiations. When I’ve discussed this with peers in hopes of finding answers, some encouraged me to be flattered, brushing concerns aside. There is nothing flattering about someone threatening your business. It’s important to note I’ve been on both sides of copying, experienced both the sweet and the very, very salty.

“I think there are shades of copying that are beneficial, appropriation that benefits the borrower and the borrowee. Adversely, I argue that shades of theft are also detrimental. While the law punishes 1:1 copies, it doesn’t safeguard against damaging, highly unethical theft at various levels.”

Why We Don’t Discuss Theft

I am not the only person to grapple with creative identity theft. The practice has occurred for millennia, many bar fights won and lost over this time honored SNAFU. We can mostly agree that out-and-out duplication from one artist’s site to another (or to a business’s point of sale) is irrefutably vile. But is there space to discuss copying/imitation/replication?

This topic is undiscussed for a couple reasons, the first being that established artists want to avoid widening the chasm between amateurs and professionals at all costs. Professionals want others to succeed because we collectively benefit and feel compelled to return on the help we received. It’s easy to pinpoint a newbie’s location on their career arc based on our own past experiences; we see ourselves in them, and want to ease their frustrations and fill them with confidence. Nobody delights in reaching out to smack a wrist or tell someone they need to re-evaluate their decision-making. It sucks. I’ve had to send these emails, and I’ve received a gamut of responses, ranging from “I’m so sorry, I cried because I’d hate to do this to someone,” to the current situation.

“There’s a fear the offended artist will try to halt what traction the amateur has made; Twitter occasionally lights up like a battlefield with these types of firefights. I took this fear to an extreme in my early career, refusing to publish anything that bore resemblance to anyone I admired...the result was years working mall retail. Extreme avoidance is self-defeating.”

From the amateur perspective, a tough word from an influence can squelch the desire to experiment. Nothing makes finance look more attractive than a scolding email from an admired peer. There’s a fear the offended artist will try to halt what traction the amateur has made; Twitter occasionally lights up like a battlefield with these types of firefights. I took this fear to an extreme in my early career, refusing to publish anything that bore resemblance to anyone I admired in the event they’d reprimand me and remember years later if/when we met; the result was years working mall retail. Extreme avoidance is self-defeating. There must be somewhere viable in the middle margin.

The uniting factor is this: we’ve all overcome struggles to create for a living. Our pedigrees, common sense, economic background can push against us. Few creatives wish to add to another’s obstacles; the decks stacked against us are high enough.

Subtractive vs. Additive Imitation

There’s a spectrum of imitation out there, one with two poles and a very hazy middle ground. Most creatives are familiar with subtractive vs. additive art forms; subtraction is used in sculpture, editing a preexisting hunk of clay into something beautiful, whereas additive is used in painting, starting with a blank canvas and applying medium to make something new. Creativity can result from both poles, the validity dependent on where you land in the middle.

Unless you were lucky enough to take a masterclass like mine, our first inclination is to take a subtractive approach to referencing others. We start with someone else’s work (replication) and strip away pieces, things we deem insignificant, until we feel it’s not theirs anymore. However all artists recognize the minute details within their work — probably from staring into the original concept until their eyes bled — therefore the reference image is always discernible. This is a poor approach. Imagine a well-meaning museum visitor chipping away at the hair and limbs of a Michelangelo sculpture (hey, it’s happened before), reducing the art to a sad pile of its former glory. Did this sculpture become any less his, or any more theirs for that matter?

Agence France-Presse Getty Images

Rather we should consider borrowing as an additive process, snagging philosophies, business practices, and micro techniques from others outside of our immediate market to our own work, thereby making it new. The inherent challenge with an additive approach is the requirement of starting with one’s own work. With an additive approach, rather than starting from a single outside source, the artist has the opportunity to integrate multiple people and multiple references into their point of view.

“With an additive approach, rather than starting from a single outside source, the artist has the opportunity to integrate multiple people and multiple references into their point of view.”

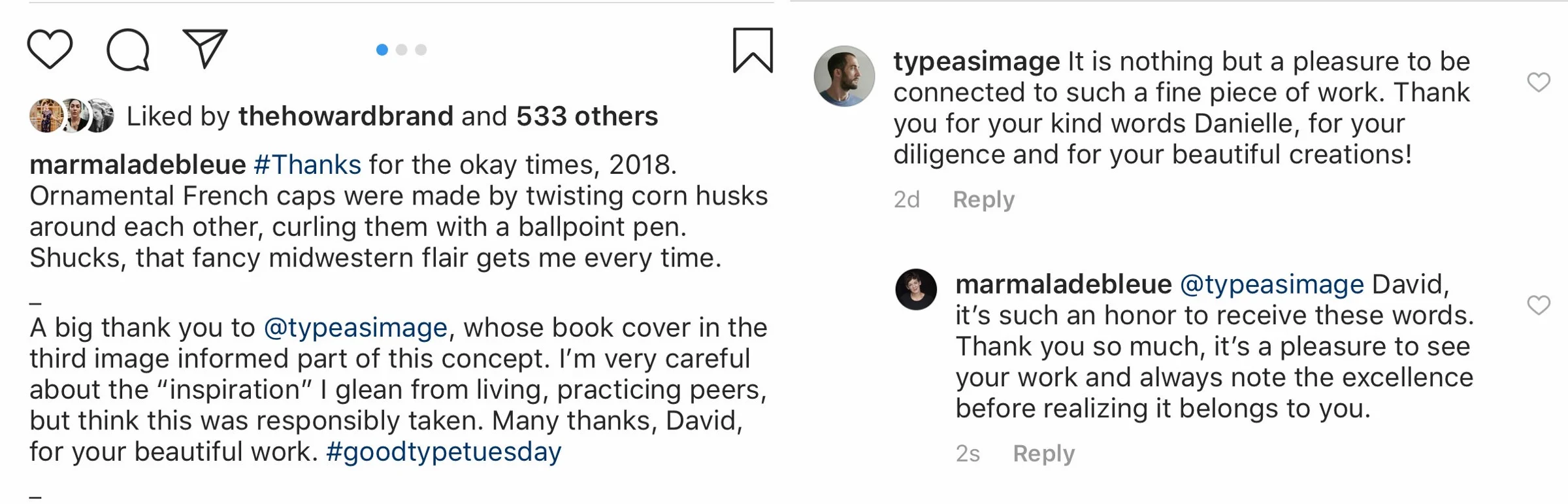

If I’m going to rant about this, I’d better be willing to post an example of additive process from my own work. Usually my work is born out of former projects, but in this case I was walking through my neighborhood bookstore and backpedaled three steps to marvel at David Pearson’s gorgeous cover for Emerson’s naturalist classic, Nature. I’d been milling on a Thanksgiving concept after a trip to a pumpkin patch, shoving ears of corn into my pockets, and this cover clarified the direction for me. This is what became “THANKS” in corn husks, ornamental French inspired caps, stacked formally on a wheat colored pine board. You can see some clear overlap in the “T”, ”N”. Note there was no way to migrate David’s line work; I had to build everything from scratch in a completely different medium.

My work on the left, influenced by David Peason’s Nature Cover for Penguin Books.

Some important details: David and I are both professionals in completely different markets, styles of execution, and geographical regions (he’s also very experienced and well-known, but I digress); this became a thank you card I sent to past clients, not a client project based on David’s work; most importantly, I’ve been linking David’s site whenever I’ve published this piece, but I tagged him directly in an Instagram repost, and he validated my efforts.

Syd Weiler, former Adobe Creative Resident and creator of Trash Doves, has braved her fair share of theft in this informative article. In asking her opinion on my subtractive vs. additive argument, she provides an excellent footnote.

“The difference between the two philosophies, subtraction and addition, is responsibility.

If you’re working subtractively, you’re taking things. Sneaking around, hiding influences. If you’re thinking additively, you’re being open about those things. You’re thanking them, sharing and building upon them.

At the end of the day, the product might be the same, but they were birthed from different intentions.”

I hear the statement “there’s nothing new under the sun,” often. While I believe this is true, we tend to use this as avoidance rather than an effort to check our egos. There is a lot of bravery wrapped up in finding one’s creative voice; style is calculated rule-breaking, observing the standard and opting out of structure based on personal taste. Those of us with discernible style grapple with this bravery when we self-publish, combatting the chronic nagging of “I know how it should be done, but I did it this way.” This is likely the root of imposter syndrome. Our individualism feels like a liability when it is in fact our strength.

“There is a lot of bravery wrapped up in finding one’s creative voice; style is calculated rule-breaking, observing the standard and opting out of structure based on personal taste. [We] grapple with this bravery when we self-publish, combatting the chronic nagging of ‘I know how it should be done, but I did it this way.’ This is likely the root of imposter syndrome. Our individualism feels like a liability when it is in fact our strength.”

When employing copying techniques, it’s important to ask if you final product adds or detracts to the legacy of those you borrow from. Are you adding value to anyone other than yourself? Your audience can’t tell you this, by the way. The truth of something is evident in how many layers deep it penetrates; in this case if you’re stealing ideas from another artist, hiding the influence, then receiving pushback once they discover your theft, you don’t know how to steal correctly. If you continue to make a career of this type of theft, rest assured it will be short.

Niche is an Old School Idea

Artists act as conduits, drawing others with likeness of heart or hopes of fame with the light of their voices. Often we call these similar bands of artists niches. Back in the day, these niches were known as schools, branches streaming from a singular source. In this way, the source transcended from a singular person to a philosophy. Louise Fili is one of the most obvious examples in modern lettering history, birthing some of the most prominent names in the industry through exposure to her vast ephemera collection and prolific body of work. You could dub her legacy the New York School, which is reliant on deco architecture, turn-of-the-century packaging, and European travel themes. Her students differentiated themselves by visual language, subject matter, distance in time from Fili and respectively contributed to a prevalent trend.

Poet T.S. Elliot’s famous and (lol) oft-misattributed quote summarizes the parameters of schools wisely. Sub “poet” for “artist” in a visual sense.

Notice the final statement, a series of differentiators. Time, subject, language. Not color, lighting, copywriting. Broader macro-factors like medium, typographic style, and subject matter can guide the creative output in a general sense, ensuring that similar portfolios still lack congruence. Overlap to some degree is inevitable, coincidental explorations are a natural result of people working closely within similar parameters. Usually these convergences occur once or twice between individuals in the same field and are born from deviation of style, a desire to experiment. Like lightning, similarity can strike occasionally with multiple people in a school. When the overlap continually occurs, the question of source material begins to mount. Coincidence is no longer an option. The Internet has expounded and muddied this overlap, but the argument still holds.

Proximity (meaning distance) reduces the potential of bad theft. This distance can be found in the above: industry differentiation, chronological overlap, subject matter, etc. Keep your distance from source material in a healthy way.

The Nature of Growth

Ever wonder why some established artists run from the spotlight, preferring “quiet work with their hands”? When we idolize someone, we strip them of their humanity. They become an idea and in a metaphorical sense a rainforest of rich, professional resources; we proceed to mine them for ideas, popularity, opinions, trade secrets. This siphon is easier to manage in real life but add the augmentation of the Internet and burnout is inevitable.

Is there a way to symbiotically nourish these people while using their experience and wisdom to aid our growth?

“When we idolize someone, we strip them of their humanity. They become an idea and in a metaphorical sense a rainforest of rich, professional resources; we proceed to mine them for ideas, popularity, opinions, trade secrets...Is there a way to symbiotically nourish these people while using their experience and wisdom to aid our growth?”

Back to the nature metaphor — an established artist is like a flower on a branch. The novice is a bud on the same branch of the initial blossom. If the branch is pruned before the flower, another can grow divergently. Proximity matters. At a healthy distance this furthers the growth of the plant; too close and the new bud ekes energy from the first bloom.

If the school is like a tree, the budding artist recognizes its roots and avoids crashing into the first flower as it unfurls, twisting its path into open sunlight to blossom at its fullest capacity instead of a half-existence in shadow. The fullest, oldest bloom may not grow the highest, and that’s okay. The first bloom has already fully opened and won’t impede the bud’s new growth. An observer may not notice the subtle differences between blooms but will appreciate a full, healthy plant.

If we can agree there is enough work to go around, one can counter-argue there is enough space and limelight in which to grow. There is no need to leech.

One clear takeaway from this passage: borrowing consistently and directly from peers actively working within our niches, vying for congruent markets is unethical and amateur. Art critic Jerry Saltz beautifully sums up long term borrowing in his 33-point guide on how to be an artist:

If someone says your work looks like someone else’s and you should stop making it, I say don’t stop doing it. Do it again. Do it 100 times or 1,000 times. Then ask an artist friend whom you trust if your work still looks too much like the other person’s art. If it still looks too much like the other person’s, try another path.

The TL;DR Case for Copying:

Should we copy? Yes. Are there parameters for doing so? Definitely.

Learn from your masters stroke for stroke in the privacy of your own study. Not everything is made to be published.

Adapt work responsibly in an additive way, starting with your own idea and layering in influence and style from personal experience. When possible, pull reference from different industries, historic periods, and cultures.

Cite your sources directly. Seek to honor them by adding without subtracting from their legacy or energy.

If you participate in the professional marketplaces with your social media, proceed with caution or refrain from publishing heavily derivative works.

Don’t be a dick.

I would love to see the creative industry expand its conversation of theft, acknowledge its precarious role in our history, and explore how we can adapt the discussion to account for global visibility. If you’ve experienced similar things, please reach out via twitter. I’d love to dialogue with you.

WNW Member Danielle Evans is an art director, lettering artist, speaker, and dimensional typographer. She’s worked with the likes of Disney, Target, the Guardian, PWC, (RED), McDonald’s, Aria, Condé Nast, Cadillac, and would love to work with you. Subscribe to her newsletter here.

Header Illustration by WNW Member Yifan Wu